Welcome to the book club. Like each book club story on this blog, the reading and commenting is done at your own pace. Have fun and enjoy!

Here we are with another early edition of a George R.R. Martin story that blurs the edges of warfare and who has the upper hand… until a programming error creates a tactical blunder.

The autotanks in this story are rather akin to the ‘power wagons‘ of And Seven Times Never Kill Man, which are truly just dragons in fantasy-land. This tactical blunder brings to mind just how closely Aegon VI will head Tyrion’s Cyvasse advice while in Westeros, and if Tyrion truly was setting Aegon up to fail.

Readers and theorists of A Song of Ice and Fire will immediately recognize the repeating themes of desolate war plains, ice versus fire dichotomy, water and rivers, duralloy (Valyrian steel), sulfuric-inferno (dragon) winds, view screens (flames of R’hllor in ASOIAF), and even a very Stannis-like commander/s showing us GRRM had been developing Stannis for a long while. This commander is even trying to maneuver war vessels called ‘juggernauts’, as Martin has used ‘dreadnaughts’ in other stories. The etymology of the suffix -naught means; From Ancient Greek ναύτης (naútēs, “sailor”). SuffixEdit. -naut. Forms nouns meaning voyager or traveller.

The Melisandre/Littlefinger archetype of a schemer who is (mis)directing the commander makes an appearance here… dang it! And there are even a few references to the cold “circulating” in the huge room, which when you read the whole scene, it reminds one of the exceptionally cold and dangerous cold that the Others (=ice dragons) bring before they invade. And the way Eddard Stark “melts” when the ice-man gets to the hot King’s Landing.Bran sitting on the dais during the Autumn festival watching Old Nan break crust is somehow taking on new meaning. As is the idea that a god is “overriding” Theon as he walks to the Weirwood trees, and Stannis will convert from fire to ice. If you are not familiar with the Theon sample chapter from The Winds of Winter, it is here for you to read.

My fave detail is that the sun is bluewhite… hmmm, a blue-white sun?

I typically makes my own notes along the way as I transcribe, but I have yet to do that with this story. So, feel free to read and share without my comments… for now (mwa-hahaha!)

I typically makes my own notes along the way as I transcribe, but I have yet to do that with this story. So, feel free to read and share without my comments… for now (mwa-hahaha!)

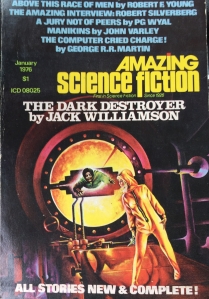

All writing credit goes to George R.R. Martin. Inside panel illustrations credit goes to Tony Gleeson. Cover artist Stephen E. Fabian. This story is being transcribed from the January 1976 edition of Amazing Science Fiction. And a short reminder that I keep all of the typos and weirdo punctuation and such as is because I don’t want to mess with 70’s print perfection.

I have started a book club re-read for the older works of George R.R. Martin for purposes such as research, scholarship, and teaching. I own all copies of material that is used for this book club. If you have not yet read a story listed, please check with your local bookstore for your own reading material to purchase (Indie Bookstore Finder, Bookshop.org, or Martin’s website). The full list of GRRM stories outside of the A Song of Ice and Fire series that I have read can be found on this page here.

It takes a while to transcribe and then note each story for research purposes, even the really short ones, so the MAIN BOOK CLUB page will be updated as each re-read is added. Make sure you subscribe for updates.

If there is a story in particular you would like to ask about, feel free to do so in comments below.

If you prefer to listen to a podcast that gives synopsis and analysis of stories written by George R.R. Martin, please consider the new group A Thousand Casts to accompany your ears. Twitter or Podbean.

The Computer Cried Charge!

George R.R. Martin

THE AUTOTANKS drove across the hellplain in a double column of fifty, towards the distant mountains where the enemy lay in wait.

Ugly was the word for the autotanks. Low, hunched shapes of battledark duralloy, they crawled on woven metal treads over ground that would have melted anything else. Screechgun mounts and the snouts of lasercannon broke their unpleasant symmetry.

Even the dull sheen of their armor was gone, hidden by the thick black heatgrease that oozed from within, shielding them until it cooked and cracked and was covered by a fresh layer.

Beneath the hardened grease: a foot of metal, then a tangled web of weaponry and circuits and motors and computers. Beneath that; the deep-buried synthabrain, fist-sized mind of the autotank. Within that: the programmed mentality of a bloodthirsty moron.

Ugly was the word for autotanks. On most worlds they were an obscene intrusion, a blot, hideous things that crushed out life beneath them with only a rumbling purr, nightmare shapes that touched beauty and left ruin.

Here they belonged.

They moved across a flat, fissured plain of yawning desolation and unending heat. They moved in a world where water was a legend and the rivers ran with white-hot metals, over rocks that hissed at the touch of their treads, around lakes of molten magma. They moved in an awful stillness, save for when the winds came. And that was no relief, for those screaming sulfuric blasts would cook the heatgrease and rip it off and sear and pit the duralloy beneath.

Across the face of the inferno, the autotanks crawled like a line of fat black slugs, ignoring the bluewhite burning blindness that filled up half the sky. Behind then they left a trail of hardened grease cooking on the rocks.

Above: it was not hot in the command center of the dropship Balaclava, and the hundred-plus men working there knew it. They knew the ship was high in orbit, safe in the cold, womb of space. They could see the readings on their temperature gauges. They could hear the faint whine of the pumps and cooling systems that kept the air circulating in the huge, bustling room.

Yet, in despite of all this, they squirmed and sweated and loosened the collars of their uniforms. They knew it was not hot, but knowledge was no defense. For the main viewscreen filled the entire forward wall with a scene from hell, and they could see the lava and the great blue sun that was larger than the mountains and the rocks that baked and cracked and hissed. And the bluewhite brilliance flooded the command center and beat at their eyes, and they could see and feel the heat that did not exist.

The worst off were the men along the port wall. When they ignored the main viewscreen and tended to their instruments, the same sun pounded at them from a thousand smaller screens. And they had to watch; each screen was the eye of an autotank, down on the face of hell, reporting what it saw.

The telecom men along the starboard wall were much better off, for they watched only blinking lights and wavering lines and dancing needles. But they’d forget at times, and look up at the main screen, and then the heat would wash over them in a torrid rush.

The computer techs were the best off, The dropship’s Battlemaster 7000 Tactical Computing System took up the wall directly opposite the main viewscreen; tending it, they had their backs to the sun at all times.

General Russ Triegloff, drop commandment, wasn’t so lucky. Moving around the mountainous holocube that filled the center of the room, Triegloff faced the screen as often as not. He was a huge, hairy man, and his brown uniform was already soaked with sweat.

He’d asked Captain Lyford to cut the main viewscreen at least twice. But Lyford , a lean hawk-faced Navy type who wouldn’t condescend to perspire if you paid him for it, had politely declined. He was very cool. He’d gotten the dropship into orbit without incident, and now he just wanted to sit back and watch Triegloff worry- and sweat. Every time the General mentioned the heat, Lyford would point to a thermometer and cluck and tell Triegloff that he was working too hard.

So Triegloff had given up on that particular crusade; he had bigger things to worry about. Flanked by a couple of under-commanders and a host of orderlies, he stomped about the room relentlessly, watching the holocube from a dozen different angles, studying photos of the enemy positions in the mountains, and thinking furiously.

He calmed a little when Lee Williston, the portly blond civilian who headed the TCS experts, fought his way through the underlings and slapped a stack of computer printouts into Triegloff’s hand. “There’s seven assault plans there,” Williston said. “Projected likelihood of success ranges from thirty-seven to seventy-two per cent.”

Triegloff moved to a desk beside the holocube, and spread the seven printouts alongside each other. “That’s not bad,” he said, studying the plans with quick familiarity of a man who has done this a thousand times before. “The seventy-two per center has the highest casualty rates, of course.”

Williston nodded. and his double chins bounced. “Of course. And that casualty figure includes men and material.”

Triegloff looked up, and brought his grizzled eyebrows together, “Men?”

“Yes. Plan four- that’s your seventy-two per center- calls for landing a couple battalions of assault squads to supplement the armor. That means human casualties, naturally, and pretty high ones.”

Triegloff picked up plan four and looked at it carefully. “Yes, I see,” he said, flipping through the pages. “I’m tempted, too. Don’t like having nothing but autotanks and juggernauts down there. They’re tough enough, but not too smart. Can’t think on their feet, like a man could, y’know?”

Williston returned a fussy frown. “The war machines will do the job for you, General, if you just program them correctly. I wouldn’t recommend choosing plan four, really I wouldn’t. The casualties are quite high. Battlemaster has given that plan a ‘least recommended’ rating, despite the high success figure.” He pointed.

“Still,” said Triegloff. “Men would give us so much more battlefield flaxibility…” He dropped the printout back to the desk reluctantly. “Well, what else is there?”

“Six other plans,” said Williston. “Two have success indices below fifty, however, and I’m sure you wouldn’t want them. That leaves four reasonably sound tactical approaches to those emplacements. All of them are roughly equal, except for a few variables.”

“Such as?” Triegloff said.

Williston shrugged. “Holes in our data, General. We don’t know everything about the enemy position we’d like to know, and Battlemaster’s projections can’t be fully reliable without full information.” He paused and looked around. “Anyone have those photos?” he asked.

An orderly shoved a stack of blown-up aerial photos at the computer man. Williston took them and turned back to Triegloff. “Here,” he said, jabbing at a photograph. “These black holes in the cliffside are the biggest problems. Until we know for certain what they are, we won’t know which plan to push.”

Trigloff, still studying the printouts, barely glanced at the photo. “I can guess what those holes are, ” he said gruffly. “We picked up energy readings from that area. And not from those big laser turrets, either- those are clearly visible. I figure we got hellglobe tubes down there, built right into the damn mountains.”

“Yes, that is a possibility,” Willistion said. “In which case, that whole valley would get a fortification index of four-oh-seven-six. Your autotanks would be decimated attacking something like that; you just don’t mess around with those sorts of figures. If those are hellglobe tubes, plan two is optimal.”

Triegloff glanced at plan two. “Right,” he said. “A joint autotank-juggernaut assault. Should do it. The juggernauts could use their shields to cover the tanks.”

“Exactly,” Williston said. “However, it’s also possible that those holes are caves, or some other natural formation. Or perhaps the only inside is more lasercanon. In that case, the fortification index drops to two-two-oh-nine. And plan seven becomes optimal.”

“No,” Triegloff said firmly. “I don’t care what Battlemaster projects; those are hellglobe tubes. I know it. A hunch, but it makes sense. That valley is the main approach of their whole sector HQ, It’d be held with everything they got, and they got hellglobes.”

Williston was about to say something, but a hand on his shoulder shut him up. Captain Lyford, smiling and immaculate in fleet-black, stepped around him and clucked at Triegloff. “I still say we should just lob them to slag from orbit,” Lyford said smoothly. “It would save you ever so much trouble, General.”

Triegloff grimaced. “Crap,” he said. “We want them alive. That’s the job. They pulled a fast one, sticking their sector base on a freakish hellhole like this without even a fleet to guard it. And they cost us plenty when we hit the fake that was supposed to be their HQ. Now they pay, though; we can grab all their top brass.”

Lyford dismissed that. “Whatever you like, General,” he said. “I got you here for the drop, so I’ll leave the rest up to you. I really should butt out, eh?”

“Your advice is always well taken, Captain,” Triegloff said with a wooden voice. “I owuld appreciate it if you would shut off that damned viewscreen, however. I really don’t need it.”

Lyford smiled. “Why? It gives a good idea of the terrain down there. But if you insist… I mean, I wouldn’t want to bother you, or impair your judgement.”

Treigloff frowned, annoyed. “My judgement is not in the least impaired by your viewscreen, Captain,” He said. “It’s only that it bothers my men. I’ve made decisions under conditions much worse than this.”

He looked down at the seven plans, very decisively, and moved his finger from one to another. There was brief pause when he touched plan four. But he moved on, and picked up plan two.

‘Here,” he said , giving the printout to an aide. “Have them program this one.”

Forward, ever forward, moved the autotanks. The mountains, once a smudge on the distant eastern horizon, now loomed larger and larger ahead of them. And still the double column drove forward, hissing and rumbling, fighting the sulfurwind and the blinding light and inexorable heat. Only ninety-nine of the column had made it this far; one ‘tank’ was miles behind, alone on the plain where it’s coling system and motors had failed almost simultaneously. There it would remain until its heat grease finally ran out, and the wind and the sun got at its duralloy flanks to burn and tear.

The others drove on without it. Now, programmed from above, they had a purpose. Now they had a battleplan.

North of them, other long rows of shapes moved in the distance, gradually growing larger. No alarms rang in the autotanks. Dimly, they knew what the other were; a second column, angling southeast to join them. The rendezvous had already been programmed into their consciousness.

Two formations paralleled each other for a long time, driving east on opposite sides of the great crevasse that divided the plain. Once, briefly, they lost sight of each other, when a second, smaller fissure branched off from the main one, and forced the southern formation to make a wide detour.

The other columns waited, however; slowing where the crevasse ran into a lake of redblack magma, and swinging around it. On the shores of that lake, they were augmented by yet another formation of autotanks that had come boiling from the northernmost dropoint at breakneck speed. Beyond the lake, on its eastern banks, the original group finally met and melded with the others.

Now six columns of autotanks resumed their drive towards the enemy, through terrain that grew steadily rougher and more difficult. The mountains ahead had become a row of blackened teeth that bit the bluewhite sun.

Triegloff leaned forward over the corporeal, his palms sweaty where they gripped the leather of the man’s seatback, his eyes fixed on the readings and the small viewscreen. There was nothing much to see on the screen: a sea of slow moving black, crossed by very thin, very faint lines.

The other instruments were more informative, and their readings spelled trouble. Triegloff watched in silence, until he suddenly grew aware that Williston was standing beside him.

“The fucking crust broke,” Triegloff said, loudly, without looking at the TCS man. “I’ve got three juggernauts covered by magma.”

Williston said nothing. Battlemaster had chosen the dropoints for each component of the attack force. If the juggernauts had been traveling over ground too weak to support their immense weight, the computer was to blame- at least in Triegloff’s eyes.

“We’re still functional, General,” the corporeal said, his attention on the instruments that were monitoring the fate of one of the buried juggernauts. “The duralloy is holding, and I’ve thrown the cooling systems onto emergency maximum. But the treads can’t get any traction, sir. And the readings are edging up towards critical. We’re got to get out soon, or we’ll have failure.”

Triegloff nodded. “How much time?”

“A half hour, sir,” the corporeal said. “Maybe a little more.”

“Leave them,’ Williston suggested.

“I intend to,” Triegloff said. “A rescue is out of the question– another section of ground might break through, and God knows how many more juggernauts I’d lose then.”

He turned away from the monitors and faced Williston. “But I’ve ordered the whole company full-stop. That’s not solid rock at all; we were moving over a goddamn sea of magma, covered by a crust of hardened rock. Can’t go forward.”

Williston looked slightly embarrassed. “I’m sorry, General, but Battlemaster can only work with the data it’s given. Our sensor readings indicated that route was solid all the way. We’ll have to recompute.”

“Damn straight,” said Triegloff, his tone very disgruntled. “I’m ordering the whole juggernaut squad to edge back, real slow and careful. Take some new readings, and find a branching where they can cut off to a new route.”

Williston nodded and moved off quickly, and Treigloff headed back to the big holocube. The holo was a constantly-changing computer simulation, assembled by Battlemaster from the data flooding the monitors. It looked almost like and aerial view. Triegloff watched intently. The pattern that had been forming, the attack pattern, was now broken.

“Sir?”

He turned to face an under-commander, wincing as he looked towards the main screen. “Yes?”

“Should we reprogram the autotanks, General?”

Triegloff hesitated. The sudden snafu had ruined the timing of the assault; the juggernauts would never make the planned rendezvous in time. And without the huge juggernauts and their cumbersome shield machinery, the enemy hellglobes would tear up the smaller autotanks in the attack.

“Waiting won’t do any good,” Triegloff said. “It’ll be hours before we get the juggsa round the magma. Have your autotanks proceed as planned, colonel.”

“The the attack point, sir?”

Yes, ” said Triegloff. He waved for the colonel to follow him and strode off down the lenth of the holocube, towards the big viewscreen. Twenty paces brought them to a section of the cube that showed the enemy fortifications. Treigloff barked to a halt, and pointed.

“I’m sticking with the plan we’ve picked,” he said. “We’ll run it through Battlemaster once more to be sure, but I don’t think there’ll be any problems. Instead of attacking at once, though, we’ll use the autotanks to soften ’em up a little until the juggernauts get there.”

His hand went into the holocube, and stroked a series of low ridges that bracketed the entrance to the most heavily fortified valley. “We’ve picked up minor energy readings from these ridges– probably low-grade stuff like disruptors and small lasers. Not too important, but they may be bothersome when we charge up the valley– and we’re going to have do that sooner or later. So we might as well knock out the ridges now. Have the autotanks swing by and plaster them. Then move out of range, quick; I doubt they’ll waste helldogs at that distance, but there’s not sense in taking any chnaces. Raid ’em like that a couple of times. And then when the juggs get there, we can reform and carry out the attack plan.”

The colonel nodded. “Sounds good, sir.” He noted the coordinates and turned back to his sector. Triegloff, already engrossed in larger considerations, hardly noticed him go.

The colonel relayed the order to the six captains under him. Each captain commanded an autotank attack group a hundred strong. The captains talked to their lieutenants, who did the actual coding. The lieutenants worked out a joint program, and handed it over to the enlisted men on the monitors, who fed it into the command consoles. The consoles chewed up the program, digested it, and spat it down to the autotanks. Then the ‘tank computers took over, deciphering the string of impulses and feeding the orders to the synthabrain.

Somewhere, somebody made a mistake.

THE LAST RENDEZVOUS was in sight of the valley, when the two big ‘tank formations, each comprised of three attack groups, linked up to form a single angry metal horde. With that last linkage, the columns broke, and the autotanks assumed battle formation: they covered the last miles in a sprawling arc.

Onward they drove, across death-still rocky foothills and smoking fissures and burning craters, towards the cliffs and ridges and the valley ahead.

Onward they drove, towards a row of silent mountains that gleamed bluewhite like sharpened teeth, and half-seen emplacements that dotted the peaks like cavities.

Onward they drove, rolling into darkness for the first time when they entered the long shadow thrown by the mountains, moving towards the dark gash in the mountain wall and the ridges that ran across it.

When the ridges were almost a mile away, battle began.

The enemy opened fire first; tiny lights began to wink and blink on top of the ridges, and laser fire spat from the shadows. The autotanks took the light blows, and drove on. The fire grew heavier. ‘Tank instruments recorded disruptor fire, and from somewhere a buried projectile gun opened up, and the ground took the explosions.

The autotanks closed, relentless. It takes a lot of force to dent duralloy. It takes a lot of heat to cut duralloy. The ridge guns came up short on both counts. The ‘tank shrugged a path through the explosions with only a few dented plates. They ignored the disruptors, light personnel weapons that were useless against armour. They worried about the lasers, but only a little; their own lasercannon were bigger and more deadly then the guns on the ridges.

Half a mile from the first ridge, the autotanks opened up. Heavy laser fire sliced into the ridges, HE rocked the gun emplacements, and the sulfur-winds shrieked with the sound of screechgun fire.

The lead ‘tanks fired first; then the others behind them; then the ones behind them. The ridges smoked and shook and the enemy guns died and grew silent. Here and there and autotank died too, but those losses were few. The ‘tank fire grew steadily heavier, more deadly. Whole sections of the ridges vanished under the pounding; rock cannot absorb punishment like duralloy.

The lead ‘tanks reached the first ridge and rolled over it, still firing. The rest of the formation followed in wave after smoking wave. They climbed over the second ridge, and third, silencing any enemy guns that still moved. They didn’t have to climb over the final ridge; it had ceased to exit before they reached it. But they climbed through the debris.

And onward drove the autotanks. Onward, not back. Onward past the ridges, past the light guns they were ordered to charge. Onward, towards the shadowed valley that yawned before them like the mouth of death.

IT HAD grown very silent int he command center, but Treigloff hardly noticed. He was absorbed in the new printouts that Battlemaster had just spewed forth, detailing alternate battleplans that took into account the delay in getting the juggernauts into action.

He snapped into awareness when an aide put an uneasy hand on his shoulder. “Yes?” he said.

“Sir,” the aide said. He looked up, at the main viewscreen.

Triegloff followed his gaze with narrowed eyes. He saw what he’d expected to see; a battle scene, confused. The autotanks had been assaulting the ridges, as he’d ordered. He hadn’t been following the action closely, although he was vaguely aware that it was in progress. Making sure the preliminary went all right was a job for his subordinates; Triegloff was planning the main event.

He had been looking at the screen for a full minute before it hit him. The autotanks were climbing over the ridges. And they were continuing.

“They’re charging,” someone said, very faintly, across the room. “They’re charging the main guns.”

Triegloff’s fists tightened. His eyes roamed the room, found the colonel who commanded the autotanks. He moved to him in a raging rush. “What the hell are you doing?”

The colonel stared. “I–a programing error. It must be a programming error.”

Triegloff looked back at the screen. The lead ‘tanks had entered the valley. The others were following in waves. “Damn you,” Triegloff shouted. “Don’t just stand there! Countermand those orders, quick.”

The colonel nodded, but didn’t move. Triegloff grabbed him with both hands, and shoved him towards the monitors. “Move it! Or you won’t have a command left…”

ONWARD drove the autotanks, over ridges and through the shadows, up the rocky valley of hell towards the pockmarked cliffs ahead. And one by one, they began to die.

The enemy waited until three-quarters of the ‘tanks were in the valley, waited while the ‘tanks pounded the cliffs with HE and scortched them with lasers, waited long minutes while the charging ‘tanks did their worst. And then, all at once, they commenced slaughter.

It was never a battle; never; never for a moment. It was just destruction.

From both sides of the valley, lasercannon opened up simultaneously; big lasercannon, the great granddaddies of the small ridge guns. The valley floor shattered under the impact of a hundred sudden explosions.

And– from a wide black hole in the cliff at the end of the valley– something shot in a fiery blur. The other holes around it spat other fire blurs. Then the first hole spat again. The the others.

And when the blurs hit and expanded and roared, shimmering globes would appear around them to hold the fire and the heat. And the targets.

Hellglobes: nukes were all they were. Nukes set off in close proximity to a big shield generator, generator that would catch the awful energy and hold it tight at the moment of its release. H-bombs in a force fist.

A disruptor can’t touch duralloy. Explosions rarely dent it. Lasers take long minutes to burn through. But catch a duralloy autotank in a hellglobe, and it writhes and melts and vaporizes in microseconds.

It takes a mountain to hold a shield generator big enough to make hellglobes, the shields have to be enormously strong. The range isn’t very good, either; you can’t throw a shield much further than you can see. But it’s worth it. The only defense against hellglobes is to make sure they don’t reach you. The huge juggernauts could have done that, with the mobile shields they mounted.

But autotanks are too small for shields.

Onward drove the autotanks, onward up the valley, onward towards the lasers and tubes and hellglobes, onward into the the teeth of the enemy. And as they drove, the hellglobes ate them. In ones and twos and fours, moving or still, firing or silent; it didn’t matter. The hellglobes found them and caught them and wrapped them in arms of fire and ate them. The hellglobes that missed ate rocks and carved craters and bit chunks out of the mountains. But few missed; most of them ate autotanks.

The shadow was gone from the valley. In hundreds of places, globes of fire burned brighter than the sun; searingly, unbearably intense. It rained hellglobes.

Onward drove the autotanks, into that rain. The enemy met them with thousands of megatons of nuclear power, but the ‘tanks took it and rolled into it unwavering.

For an eternity they rolled into it, vanishing as they crept closer, swallowing up the carnage. Then, all at once, the survivors went stiff.

And they began to turn.

Retreat: or attempted retreat. But really, it was rout. Back towards the mouth of the valleythey rushed, but the hellglobes followed them and ate them as they ran. And when ‘tanks crept past effective hellglobe range, the lasers took over once again.

Still, a handful made it out of the valley.

ABOVE, on the dropship, they watched it all in living color. No one said anything. Not Triegloff, nor Williston, nor even Lyford. Until it was over. Lyford had been standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Triegloff. Triegloff wasn’t certain when he’d arrived, but he was there now. And he looked at the general and spoke. “My god, ” he said. “What happened?”

Triegloff was ashen. His mind wasn’t working properly. He kicked it and tried ot get it to think, but it was still seeing those hellglobes pouring down and down and down, and still hearing the awful whine the monitors sounded whenever one of the hellglobes caught an autotank.

Finally he shook his head. “An error,” he said slowly, his voice thick. “An– error. Somebody gave the wrong order. Somebody– they charged the wrong guns.” He shook his head again, fighting to clear away the shock. The command center was still quiet. Telecom instruments had quit chattering and all along the port wall the viewscreens were out. A few still showed that burning sun, but row on row were now dark and black.

Williston came between Triegloff and the silent, scared Lyford. He handed the General some printouts. “I’ve programmed this all into Battlemaster,” he said. “I assumed you’d be wanting some new attack plans.” He shrugged. “You’ve got three new approaches here, using mostly the juggernauts and whatever autotanks have survived. However, you’re going to have to send down some men, I’m afraid. The casualties will be very high, but there’s no alternative.”

Triegloff looked at the printouts, dully. Then up. “But– the success indices–”

“Yes,” said Williston. “Fourteen per cent to twenty-six percent, I know; not very encouraging. Still, it’s all that’s left. The autotanks were and important part of Battlemaster’s earlier computations.”

Triegloff let the plans drop to the floor, and looked at Williston very hard. “You son of a bitch, ” he said, something of his old manner returning to his voice in a rush. “Now you tell me to send men down– now when the odds are hopelessly against them. Hell! If I’f sent men in the first place, none of this would ever have happened.”

Williston was unmoved. “General Triegloff, that’s not true. You can’t blame this reversal on the machines, I’m afraid. The autotanks simply carried out the orders they were given. They attacked when you programmed then to attack, and retreated when you altered the program. Whoever gave the order was at fault, I’m afraid.”

Triegloff snorted. “Crap. Men would have had the sense to know I didn’t mean to send then up against hellglobes naked. They would have been intelligent enough to beam up and question the order, and the misunderstanding would have gotten cleared up pronto. But your damned stupid machines just went ahead and blindly did it. And got themselves wiped out, and fouled up the whole mission. No human being could possibly be that stupid.”

Down on the surface of hell, thirty-two autotanks crawled across the plain in an uneven double column. A few, seared and damaged, had already dropped behind to die. And several of the others were struggling.

But they moved on, towards the rendezvous with the juggernauts and a new battle to come. Untired and unthinking they moved on.

–George R.R. Martin

Want more GRRMspreading?

- Override– A betrayal between brothers. We are introduced to the rather well adjusted, pacifist main character Kabaraijian who is eventually sold out by his coworker/brother for money. A blood betrayal in #ASOIAF terms.

- Nightflyers– Nightflyers is about a haunted ship in outerspace. This story is everything a reader would want from a GRRM story; high body count, psi-link mind control, whisperjewels, corpse handling, dragon-mother ships, the Night’s Watch ‘naval’ institution in space, and Jon and Val.

- Sandkings– Welcome to the disturbing tale of Simon Kress and his Sandkings. Early origins of Unsullied, Dothraki, Aerea Targaryen, and Dragon who mounts the world, set among a leader with a god complex. One of the “must read” George R.R. Martin stories.

- Bitterblooms– In the dead of deep winter, a young girl named Shawn has to find the mental courage to escape a red fiery witch. Prototyping Val, Stannis, and Arya along with the red witch Melisandre.

- The Lonely Songs of Laren Dorr – Discarded Knights guards the gates as Sharra feels the Seven while searching for lost love. Many Sansa and Ashara Dayne prototyping here as well.

- …And Seven Times Never Kill Man– A look into a proto-Andal+Targaryen fiery world as the Jaenshi way of life is erased. But who is controlling these events? Black & Red Pyramids who merge with Bakkalon are on full display in this story.

- The Last Super Bowl– Football meets SciFi tech with plenty of ASOIAF carryover battle elements.

- Nobody Leaves New Pittsburg– first in the Corpse Handler trio, and sets a lot of tone for future ASOIAF thematics.

- Closing Time– A short story that shows many precursor themes for future GRRM stories, including skinchanging, Sneaky Pete’s, catastrophic long nights…

- The Glass Flower– a tale of how the drive for perfection creates mindlords and mental slavery.

- Run to Starlight– A tale of coexistence and morality set to a high stakes game of football.

- Remembering Melody– A ghost tale written by GRRM in 1981 that tells of long nights, bloodbaths, and pancakes.

- Fast-Friend transcribed and noted. Written in December 1973, this story is a precursor to skinchanging, Bran, Euron, Daenerys, and ways to scheme to reclaim lost love.

- The Steel Andal Invasion– A re-read of a partial section of The World of Ice and Fire text compared to the story …And Seven Times Never Kill Man. This has to do with both fire and ice Others in ASOIAF.

- A Song for Lya– A novella about a psi-link couple investigating a fiery ‘god’. Very much a trees vs fire motif, and one of GRRM’s best stories out there.

- For A Single Yesterday– A short story about learning from the past to rebuild the future.

- This Tower of Ashes– A story of how lost love, mother’s milk, and spiders don’t mix all too well.

- A Peripheral Affair (1973)– When a Terran scout ship on a routine patrol through the Periphery suddenly disappears, a battle-hungry admiral prepares to renew the border war.

- The Stone City– a have-not surviving while stranded on a corporate planet. Practically a GRRM autobiography in itself.

- Slide Show– a story of putting the stars before the children.

- Only Kids are Afraid of the Dark– rubies, fire, blood sacrifice, and Saagael- oh my!

- A Night at the Tarn House– a magical game of life and death played at an inn at a crossroads.

- Men of Greywater Station– Is it the trees, the fungus, or is the real danger humans?

- The Computer Cried Charge!– what are we fighting for and is it worth it?

- The Needle Men– the fiery hand wields itself again, only, why are we looking for men?

- Black and White and Red All Over– a partial take on a partial story.

- Fire & Blood excerpt; Alysanne in the north– not a full story, but transcribed and noted section of the book Fire & Blood, volume 1.

If you want to browse my own thoughts and speculations on the ASOIAF world using GRRM’s own work history, use the drop-down menu above for the most content, or click on the page that just shows recent posts -> Recent Posts Page.

Thanks for reading along with the jambles and jumbles of the Fattest Leech of Ice and Fire, by gumbo!

Hello The Fattest Leech,

That cover art by Stephen E. Fabian looks very familiar to me, but I could be imagining things.

-John Jr

LikeLiked by 1 person